...oh, look.

It's our very own London Philharmonic Orchestra, whose Australian CEO, Tim Walker, is quoted in a Telegraph article extolling the "opportunity for orchestras to escape EU red tape and re-engage with the world".

What the actual ****?

Here, in the interests of balance, is a report from the ISM corporate members' Brexit round table discussion, exploring some of the concerns at stake, including the potential loss of flexible travel, the potential loss of opportunities for higher education, the increase in bureaucracy for Brits working abroad and the general, bewildered impression overseas that Britain has lost its mind.

https://www.ism.org/blog/ism-corporate-members-brexit-round-table-1

Plus more from its #freemovecreate here: https://www.ism.org/news/parliamentary-committee-backs-flexible-travel-for-the-creative-industries-post-brexit

And here is the ABO report on the implications of Brexit for UK orchestras, which contains a great deal of very important reading. http://abo.org.uk/media/128619/ABO-Brexit-report.pdf

I have some questions for Tim next time I see him - but, things being as they are, it's all in the open, so here goes.

-- There's nothing wrong with being positive and looking for opportunities. I value your optimistic stance. But I would like to know to what extent the Torygraph has taken your words and twisted them to fit its own world view - and to what extent it has not.

-- What is the management doing to support the EU citizens who are long-standing members of the orchestra, given the current bargaining-chip status foisted upon them by our government? You have members from Germany, France, Italy, the Netherlands, Hungary, Latvia, Spain, Ireland, Sweden and Bulgaria. How do you think they'd feel if they thought you, their own CEO, were part of the movement that is making life so traumatic for EU citizens in Britain now?

-- The orchestra has long been going to China almost annually, so how exactly is this part of your brave new Brexit world?

-- How is the orchestra going to manage the costs and bureaucracy of customs when transporting its equipment if we get a hard Brexit that forces us to leave the Customs Union? This will mean more red tape in Europe, not less - as has been roundly proven many times in the past 19 months. And will the LPO lorry not be stuck on the M20 outside Dover for days in each direction, with all the other truckers?

-- In the same field, costs will be higher. Government coffers will be depleted as the City workers who can longer function here depart, taking with them the tax revenues they'd have provided. This will keep public investment at rockbottom for many years to come and in the arts the chances of your public grant increasing are frankly zilch. You'll need to fund all this from elsewhere. I do hope you're on the case?

-- How are you going to replace lost sponsorship from European organisations? We have heard rumours that a planned recording recently fell through because a sponsor decided not to stump up for a British orchestra.

-- How are you going to persuade a world-class conductor to come here and take over from Vladimir Jurowski when he goes, knowing their earnings will be worth so much less outside Brexit Island?

-- How are you going to continue to attract and retain such fine players? You will lose the interest and enthusiasm of the best young European orchestral musicians, who won't have the automatic right to come and work here. While we appreciate that there are many good foreign players in the orchestra from the Far East and America, the chances are that in the long term, standards will fall as fewer players will be applying to join.

-- Conditions for the musicians are already quite poor compared to those in mainland Europe. And most of the younger recruits can't afford to live in London; they spend much time and energy commuting from Lewes, Tonbridge and the like. How can you ever improve their lot if all that revenue disappears?

-- How are you going to replace the bums-on-seats that will fall victim to economic uncertainty and the lack of business confidence? In the end you need your audience. Numbers are already down this season; it appears that people are not buying anything in the way of optional extras, since Brexit has devalued the pound and sparked inflation with which earnings do not keep pace.

-- You have done much for this orchestra in artistic terms over the years. It's currently in better shape than I have ever heard it (with the one exception of Solti's Mahler 5 in 1988). You've facilitated Jurowski's leadership and taken excellent risks with programming. You've made the LPO, with Jurowski, into currently the best orchestra in London. All this achievement risks being squandered in the slag-heap of division that Brexit has sparked. Why? Why throw it all away?!?

-- In this article you do not categorically say you voted for Brexit, but neither do you categorically deny it. Did you, or did you not, vote to strip your UK members of their automatic right to live and work in 27 other European countries? If you did, do you believe they and their families will ever forgive you?

Monday, January 29, 2018

Marin takes Vienna

|

| Marin Alsop's selfie from the Last Night of the Proms |

Now we need more splendid conductors who happen to be female to be elevated to prominent posts, where they will be worth their weight in gold both as role models for the future and as musicians in their own right and their orchestras'. Incidentally, there may well be some London orchestra jobs up for grabs in the next few years - one of them appears to have a vacancy right now - and the opportunity will be staring them in the face. Let's hope a manager or two has the foresight to approach the right person.

Jude Kelly, as you know, is leaving Southbank Centre to concentrate her energies on WOW - the Women of the World Festival. In a thoughtful interview with the Guardian the other day, she said it's not enough to be a feminist: you have to do something.

To that end, I've done something very small that I hope will be reasonably useful: I've added a sidebar section here on JDCMB devoted to resources for women in the music world. You can use this as a one-stop-shop to click through to sources of funding like the PRS Foundation's Women Make Music and the Ambache Charitable Trust, courses like RPS Women Conductors, projects like Dallas Opera's Women Conductors Institute and more. I'm on the lookout for links to add, so if you know of one that ought to be there please send it my way, preferably via Facebook or Twitter. This is about organisations that can offer support and development to many, rather than individual artists' websites. But you'll also find there a link to my Women Conductors List (it runs to well over 100 names and sites) and that is always open to updating with individual names. Thanks very much for taking a look.

Thanks, too, for the powerful response to yesterday's shoulder post. I now have recommendations of at least 10 different osteopaths!

If you've enjoyed this post, please support JDCMB at GoFundMe here

Sunday, January 28, 2018

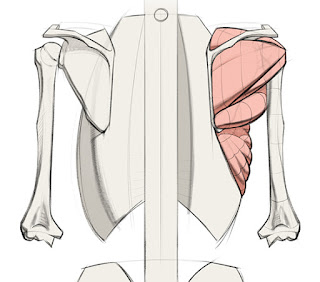

Shouldering the pain

I've done something unspeakable to my shoulder. It may be a delayed reaction to the return journey from Johannesburg last week, with bad seat position overnight plus some ungainly moves with a heavy suitcase at Heathrow. Yesterday I spent in a fog of agony and the strongest over-the-counter painkillers Superdrug could provide, thanks to which I managed to attend a wonderful performance of Das Rheingold by the LPO/Jurowski at the Festival Hall, but without much brainpower to respond.

Friends have been kindly suggesting all manner of treatments, but I'm hesitating. That's because the very word "chiropractor" brings back a whopper of a memory from my college days: my sorry year and a half trying to recover from tennis elbow as a music student, in a university that should have known better, in a town that loathed its students on principle.

It's struck me recently - notably in the Hammerklavier project and the Korngold Violin Concerto - that sometimes we don't play the music that's there. Instead, we play our attitude to it, or what we think the right attitude is. It doesn't often do musical expression much good. That's how we get "Beethoven's Hammerklavier: I Respect It But I Don't Love It" performances, as well as deeply destructive "Korngold Is Hollywood Which Is Sentimental, So Let's Add Sugar" recordings. In both cases, the notion could not be further from the composer's intentions. We're not playing Beethoven or Korngold. We're playing our preconceptions about them. Which obviously is a rather rubbish thing to do.

Why is that relevant to sore arms? Well, it shows how our minds sometimes work. It becomes relevant when the attitude being expressed in professional performance is not to a piece of music, but to a person, and the issue is not playing a concerto or sonata, but treating a medical condition. What follows is not to denigrate the thousands of excellent, devoted and disinterested health workers who look after us all in difficult conditions day and night. It is one experience that occurred 30 years ago. I don't know how widespread such experiences are - but it seems unlikely that I'm the only person who ever encountered such a situation.

The correlation of physical to mental health - and, indeed, mental attitude - is powerful and merits the deeper investigation it has received in recent years, but it seems to be still much misunderstood. And it can work both ways. Blame the physical alone and you may miss a psychological component. But any tendency to blame the mind first and foremost would risk missing very real physical issues. In the year and a half I spent trying to recover from my tennis elbow - 1986-87 - I also came down with glandular fever. The first reaction from every practitioner I consulted in that town was that "it's all in the mind". I don't know how they'd reached that conclusion when all I'd said was that I was a second-year music student, I had a sore throat and a chronic fever and my arm hurt. They sent me to the university counselling service. I sat there saying I had a sore throat and a chronic fever and my arm hurt.

If you are a music student in a place notorious for its privilege, where everyone outside those walls - including, it appeared, some GPs and some 'alternative' practitioners - expect those from the university to roll in being entitled and stuck-up, it can be very difficult to get past this expectation. They don't see the actual person. They may not even see the injury. They see what they expect to see.

I tried the Sports Injuries Unit. Yes, there are designated hospital units for people who've sustained injuries pursuing a physical activity such as sport and they'll take remarkably good care of you if you've been playing rugby or rowing or whatever. But for a painful case of tennis elbow acquired through over-assiduous practising of the Chopin 'Revolutionary' Etude, you'd be shoved in a corner with a grudging ice-pack and some slightly ineffectual ultrasound, with tut-tutting because you haven't just injured yourself that day, you've been suffering for weeks (while you tried to get appointments for some treatment), and that's not really in their remit. The psychological message delivered with that ice-pack, surrounded by big chaps with "Football Is Life" t-shirts, is roughly: sports are good and a nice hobby, so we'll support that, but what do you mean music is your life? "I got my sprain playing centre forward. What about you?" "Playing Chopin." "Yer wot?" (The Eighties were a more polite decade than the present one, even at their most objectionable.)

Then I tried a chiropractor. I found myself facing a huge bloke from Yorkshire with a face like bacon and hands like beefsteaks, who said it was all in my neck - and proceeded to make certain that it would be. He should have been a butcher. I've never experienced, before or since, such pain at the hands of another human being (and I know I'm lucky in this respect), let alone someone who charged money for inflicting it. I remember coming out of that session dizzy and nauseous, knocking on the door of the nearest friend in the nearest college and almost passing out on her floor. Perhaps he was a rogue or a quack, I don't know, but I will never, ever try a chiropractor again.

Then I tried a chiropractor. I found myself facing a huge bloke from Yorkshire with a face like bacon and hands like beefsteaks, who said it was all in my neck - and proceeded to make certain that it would be. He should have been a butcher. I've never experienced, before or since, such pain at the hands of another human being (and I know I'm lucky in this respect), let alone someone who charged money for inflicting it. I remember coming out of that session dizzy and nauseous, knocking on the door of the nearest friend in the nearest college and almost passing out on her floor. Perhaps he was a rogue or a quack, I don't know, but I will never, ever try a chiropractor again.

Back in London for the holidays, I went to the family GP who'd known me since I was born. He did a blood test - which the university town GP hadn't done before sending me for counselling - and it revealed a virus of the glandular fever type. For that, there's not much you can do except take fever-reducing pain-killers and rest up with herbal tea. He prescribed anti-inflammatory pills for the arm, which helped a bit, if temporarily, and suggested a cortisone injection. I declined because a violinist in our circle of friends had had a cortisone injection in her arm for a similar problems: a mistake was made and she was left unable to play at all. But through our family GP I should probably have accepted it. I've had cortisone injections since then, carefully prepared by disinterested medical professionals with scans etc, for other problems that cleared up instantly as a result.

Still at home, I tried acupuncture next, doing a reasonable imitation of a porcupine splayed out on a table unable to free itself of its spines. They said it wouldn't hurt. It did. They said it wouldn't bruise. It did: I came out with a plum-and-charcoal-coloured hand. They said it would rebalance the energy to make the pain better. It made it worse. I've often been assured of the wonders of acupuncture since then, by some eminent musicians whose problems have been cured by it, but I think I'll give it a miss.

One day I went into a chemist to look at various on-the-shelf remedies in case I'd missed something. In a little book called 'Homeopathy for the Family' I found a recommendation for "pains in ligaments". I don't actually believe in homeopathy, but as I'd tried almost everything else, I thought I'd give it a whirl. I bought a little bottle of tiny white pills, which cost about £1.50. Two weeks later I was better.

I'm not recommending homeopathy, though. It hasn't worked for me for anything else since. I think the difference here was that at this stage I wasn't putting myself in the hands of people who, due to an institutional loathing of young people who dared to study music and play the piano, had quite possibly set out to make our conditions worse. Such an idea was absolutely unthinkable at the time. But looking back, I can't help wondering if that was the actuality behind the scenes.

My heart goes out to musicians who are suffering physical injuries and navigating minefields as they seek a solution. Today, three decades on from my experiences, the understanding of music as a physical pursuit that can give rise to physical injuries has been transformed and institutions such as the British Association for Performing Arts Medicine, Help Musicians UK, the ISM and the Musicians' Union, as well as the conservatoires themselves, are brilliantly organised and supportive if you are unlucky enough to need treatment, advice, counselling or financial aid for time off. But it's sobering to think that after 30 years, I am still angry about what happened to me then.

Meanwhile, I don't know what I've done to my shoulder, but I am leaving it to voltarol and co-codamol for a few days and will avoid heavy lifting for a week or two. At least now I don't have to practise the 'Revolutionary' Study.

If you've enjoyed this post, please support JDCMB at GoFundMe

Friends have been kindly suggesting all manner of treatments, but I'm hesitating. That's because the very word "chiropractor" brings back a whopper of a memory from my college days: my sorry year and a half trying to recover from tennis elbow as a music student, in a university that should have known better, in a town that loathed its students on principle.

It's struck me recently - notably in the Hammerklavier project and the Korngold Violin Concerto - that sometimes we don't play the music that's there. Instead, we play our attitude to it, or what we think the right attitude is. It doesn't often do musical expression much good. That's how we get "Beethoven's Hammerklavier: I Respect It But I Don't Love It" performances, as well as deeply destructive "Korngold Is Hollywood Which Is Sentimental, So Let's Add Sugar" recordings. In both cases, the notion could not be further from the composer's intentions. We're not playing Beethoven or Korngold. We're playing our preconceptions about them. Which obviously is a rather rubbish thing to do.

Why is that relevant to sore arms? Well, it shows how our minds sometimes work. It becomes relevant when the attitude being expressed in professional performance is not to a piece of music, but to a person, and the issue is not playing a concerto or sonata, but treating a medical condition. What follows is not to denigrate the thousands of excellent, devoted and disinterested health workers who look after us all in difficult conditions day and night. It is one experience that occurred 30 years ago. I don't know how widespread such experiences are - but it seems unlikely that I'm the only person who ever encountered such a situation.

The correlation of physical to mental health - and, indeed, mental attitude - is powerful and merits the deeper investigation it has received in recent years, but it seems to be still much misunderstood. And it can work both ways. Blame the physical alone and you may miss a psychological component. But any tendency to blame the mind first and foremost would risk missing very real physical issues. In the year and a half I spent trying to recover from my tennis elbow - 1986-87 - I also came down with glandular fever. The first reaction from every practitioner I consulted in that town was that "it's all in the mind". I don't know how they'd reached that conclusion when all I'd said was that I was a second-year music student, I had a sore throat and a chronic fever and my arm hurt. They sent me to the university counselling service. I sat there saying I had a sore throat and a chronic fever and my arm hurt.

If you are a music student in a place notorious for its privilege, where everyone outside those walls - including, it appeared, some GPs and some 'alternative' practitioners - expect those from the university to roll in being entitled and stuck-up, it can be very difficult to get past this expectation. They don't see the actual person. They may not even see the injury. They see what they expect to see.

I tried the Sports Injuries Unit. Yes, there are designated hospital units for people who've sustained injuries pursuing a physical activity such as sport and they'll take remarkably good care of you if you've been playing rugby or rowing or whatever. But for a painful case of tennis elbow acquired through over-assiduous practising of the Chopin 'Revolutionary' Etude, you'd be shoved in a corner with a grudging ice-pack and some slightly ineffectual ultrasound, with tut-tutting because you haven't just injured yourself that day, you've been suffering for weeks (while you tried to get appointments for some treatment), and that's not really in their remit. The psychological message delivered with that ice-pack, surrounded by big chaps with "Football Is Life" t-shirts, is roughly: sports are good and a nice hobby, so we'll support that, but what do you mean music is your life? "I got my sprain playing centre forward. What about you?" "Playing Chopin." "Yer wot?" (The Eighties were a more polite decade than the present one, even at their most objectionable.)

Then I tried a chiropractor. I found myself facing a huge bloke from Yorkshire with a face like bacon and hands like beefsteaks, who said it was all in my neck - and proceeded to make certain that it would be. He should have been a butcher. I've never experienced, before or since, such pain at the hands of another human being (and I know I'm lucky in this respect), let alone someone who charged money for inflicting it. I remember coming out of that session dizzy and nauseous, knocking on the door of the nearest friend in the nearest college and almost passing out on her floor. Perhaps he was a rogue or a quack, I don't know, but I will never, ever try a chiropractor again.

Then I tried a chiropractor. I found myself facing a huge bloke from Yorkshire with a face like bacon and hands like beefsteaks, who said it was all in my neck - and proceeded to make certain that it would be. He should have been a butcher. I've never experienced, before or since, such pain at the hands of another human being (and I know I'm lucky in this respect), let alone someone who charged money for inflicting it. I remember coming out of that session dizzy and nauseous, knocking on the door of the nearest friend in the nearest college and almost passing out on her floor. Perhaps he was a rogue or a quack, I don't know, but I will never, ever try a chiropractor again.Back in London for the holidays, I went to the family GP who'd known me since I was born. He did a blood test - which the university town GP hadn't done before sending me for counselling - and it revealed a virus of the glandular fever type. For that, there's not much you can do except take fever-reducing pain-killers and rest up with herbal tea. He prescribed anti-inflammatory pills for the arm, which helped a bit, if temporarily, and suggested a cortisone injection. I declined because a violinist in our circle of friends had had a cortisone injection in her arm for a similar problems: a mistake was made and she was left unable to play at all. But through our family GP I should probably have accepted it. I've had cortisone injections since then, carefully prepared by disinterested medical professionals with scans etc, for other problems that cleared up instantly as a result.

Still at home, I tried acupuncture next, doing a reasonable imitation of a porcupine splayed out on a table unable to free itself of its spines. They said it wouldn't hurt. It did. They said it wouldn't bruise. It did: I came out with a plum-and-charcoal-coloured hand. They said it would rebalance the energy to make the pain better. It made it worse. I've often been assured of the wonders of acupuncture since then, by some eminent musicians whose problems have been cured by it, but I think I'll give it a miss.

One day I went into a chemist to look at various on-the-shelf remedies in case I'd missed something. In a little book called 'Homeopathy for the Family' I found a recommendation for "pains in ligaments". I don't actually believe in homeopathy, but as I'd tried almost everything else, I thought I'd give it a whirl. I bought a little bottle of tiny white pills, which cost about £1.50. Two weeks later I was better.

I'm not recommending homeopathy, though. It hasn't worked for me for anything else since. I think the difference here was that at this stage I wasn't putting myself in the hands of people who, due to an institutional loathing of young people who dared to study music and play the piano, had quite possibly set out to make our conditions worse. Such an idea was absolutely unthinkable at the time. But looking back, I can't help wondering if that was the actuality behind the scenes.

My heart goes out to musicians who are suffering physical injuries and navigating minefields as they seek a solution. Today, three decades on from my experiences, the understanding of music as a physical pursuit that can give rise to physical injuries has been transformed and institutions such as the British Association for Performing Arts Medicine, Help Musicians UK, the ISM and the Musicians' Union, as well as the conservatoires themselves, are brilliantly organised and supportive if you are unlucky enough to need treatment, advice, counselling or financial aid for time off. But it's sobering to think that after 30 years, I am still angry about what happened to me then.

Meanwhile, I don't know what I've done to my shoulder, but I am leaving it to voltarol and co-codamol for a few days and will avoid heavy lifting for a week or two. At least now I don't have to practise the 'Revolutionary' Study.

If you've enjoyed this post, please support JDCMB at GoFundMe

Saturday, January 27, 2018

Sounds of Silence - a guest post for Holocaust Memorial Day, by Jack Pepper

It's Holocaust Memorial Day and our occasional Youth Correspondent, Jack Pepper, has sent me an article for the occasion. When many of us feel lost for words even today, facing such horror, Jack (who's 18) has encapsulated the pain of these memories most eloquently. Over to him...

JD

Sounds of

Silence

Jack Pepper

Today is Holocaust Memorial Day and we should reflect on the tragic loss of musical talent amongst the

millions who were slaughtered – a loss that amounts to more than a statistic

Having visited Auschwitz-Birkenau myself, it became clear that

we can never truly comprehend what happened there. Although we musicians are

eager to speak of the undeniable power of music to heal and bring hope, our art could do little to ultimately save the lives of so many talented musicians in the Holocaust. That is perhaps what makes it so shocking. The Nazi

machine did not care for expression, talent, potential or individuals. Music is

perhaps the ultimate expression of our humanity – an “outburst of the soul”, as

Delius put it – and so it seems to me symbolic that even music could not truly

act against what happened. Music is the strongest form of expression, something

which touches people of all cultures and backgrounds; it is a sign of the

monstrosity of the Holocaust that even music was powerless to prove to the

perpetrators that their victims were normal human beings. When music fails,

emotion has failed. The “soul” has been suppressed.

For Holocaust Memorial Day, 27 January – the day that Auschwitz-Birkenau was liberated – it is right that we

reflect upon the individual stories of those who were so cruelly taken away.

The Holocaust aimed to dehumanise Jews, homosexuals, gypsies, Poles and the

disabled. In a 21st-century democracy that respects the freedom of

individuality, we remember those killed in the Holocaust not as a vast number,

not as a statistic, but as individual human beings.

A human being like Viktor Ullmann. Killed in Auschwitz in

October 1944, Ullmann’s work could not escape his circumstances. His chamber

opera, Der Kaiser von Atlantis, was

also called The Abdication of Death;

the plot describes how death has been overworked, and chooses to go on strike.

Sections of the libretto were written on the back of deportation lists to

Auschwitz.

A human being like Alma Rosé. The niece of Gustav Mahler and

the daughter of violinist Arnold Rosé, for ten months Alma was placed in charge

of the women’s orchestra at Auschwitz. When she first conducted the ensemble,

the average age of its players was just 19: one year older than me. Rosé

insisted on the highest possible standards of performance, rehearsing the

orchestra for ten hours daily. Justifying such hours was not difficult: “If we

don’t play well, we’ll go to the gas”, said Rosé. She died in April 1944. The

orchestra was disbanded by October.

A human being like Pavel Haas. Composing whilst working in

his father’s shoemaking business before the War, Haas received the Smetana

Foundation Award for his opera, Šarlatán

(The Charlatan). For this work, Haas

collaborated with a German writer, which – since he was a Jewish composer – had

been forbidden by the Nuremberg Laws. To avoid difficulties, Haas changed the

German-sounding name of the opera’s main character to its Czech equivalent.

After its premiere in 1938, the opera was not performed on stage again until

1998. Having been interned in Theresienstadt, Nazi propaganda films showed Haas

taking a bow after inmates had performed one of his operas; having been filmed

for this propaganda, Haas was taken to Auschwitz. According to conductor Karel

Ančerl, who was sent to Auschwitz with Haas but survived beyond the War, upon

arriving at the camp both musicians stood side by side. Ančerl was about to be

selected to go to the gas chambers, and at that moment Haas coughed. As a

result, Haas was selected instead.

A human being like Robert Dauber, who was just 23 years old

when he died of typhoid in Dachau. Unlike Ullmann’s chamber opera, many of the

works Dauber completed whilst imprisoned make little or no reference to his

position in a camp. Music, presumably, was an escape.

|

| Gideon Klein Photo: Orel Foundation |

A human being like Gideon

Klein, who had been forced to abandon his plans to study at university once the

Nazis had closed off higher education to Jews in Czechoslovakia. He gave his

manuscripts to his partner in the camp shortly before his death, a poignant

example of how music can so quickly become a memorial, a testament to an entire

life of work.

A human being like Carlo Taube, who before the War had made a

living playing the piano in cafes in Vienna and Prague. He, his wife and his

child were all deported to Auschwitz in the autumn of 1944. None of them

survived.

These were all real people. They had such lives ahead;

Ullmann had studied with Schoenberg, Haas with Janáček, Taube with Busoni. Imagine

what the musical world would be like without the teachers; no Schoenberg, Janáček

or Busoni. Nobody knows who their pupils could have gone on to become. An

entire future was destroyed, numerous possibilities denied. Their stories are

far more than a list of anecdotes for an article, far more than a shocking

statistic. These were all real people.

Perhaps most disturbing is that the perpetrators enjoyed

music too. Hitler famously idolised the work of Wagner, whilst Maria Mandel -

the SS Officer who created the Women’s Orchestra of Auschwitz and who is

believed to have been complicit in over 500,000 deaths - particularly favoured Madame Butterfly. Shockingly, the

perpetrators were all real people, too.

There are many stories that shock a modern-day reader, we

who are used to (and perhaps take for granted) the comforts and luxuries of

modern life. This Holocaust Memorial Day, we should remember the individuals

behind the statistics – the human stories the Nazis sought to destroy – and, in

doing so, we ensure that the aims of the Holocaust are never realised. Seeking

to destroy the humanity of the prisoners, instead the humanity was only

magnified. The existence of music in such desperate circumstances proves that,

despite the evil, somewhere there was

decency. Emotion. Empathy. Although music could not prevent such savagery, its

existence reminds us that despite chaos, killing and suffering, some people,

somewhere, maintain a flicker of humanity.

JP

Friday, January 26, 2018

WORDS AS MUSIC

If you're around north London on 10 February, please join me and my fellow musical Unbounders Tot Taylor (author, The Story of John Nightly, and record producer extraordinaire), Lev Parikian (author, Why Do Birds Suddenly Disappear?, and conductor) and Miranda Gold (author, Starlings and A Small, Dark Quiet) to discuss those glittering, magical realms in which music and literature intersect. MAP Studio Café, 45 Grafton Road, London NW5 3DU. Tickets: 020 7916 0545.

Labels:

Lev Parikian,

MAP Cafe,

Miranda Gold,

Tot Taylor,

Unbound

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)