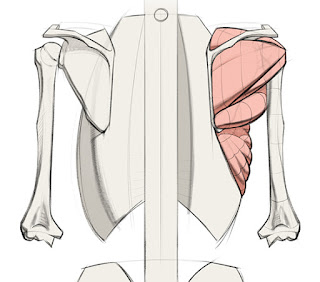

I've done something unspeakable to my shoulder. It may be a delayed reaction to the return journey from Johannesburg last week, with bad seat position overnight plus some ungainly moves with a heavy suitcase at Heathrow. Yesterday I spent in a fog of agony and the strongest over-the-counter painkillers Superdrug could provide, thanks to which I managed to attend a wonderful performance of

Das Rheingold by the LPO/Jurowski at the Festival Hall, but without much brainpower to respond.

Friends have been kindly suggesting all manner of treatments, but I'm hesitating. That's because the very word "chiropractor" brings back a whopper of a memory from my college days: my sorry year and a half trying to recover from tennis elbow as a music student, in a university that should have known better, in a town that loathed its students on principle.

It's struck me recently - notably in the Hammerklavier project and the Korngold Violin Concerto - that sometimes we don't play the music that's there. Instead, we play our attitude to it, or what we think the right attitude is. It doesn't often do musical expression much good. That's how we get "Beethoven's Hammerklavier: I Respect It But I Don't Love It" performances, as well as deeply destructive "Korngold Is Hollywood Which Is Sentimental, So Let's Add Sugar" recordings. In both cases, the notion could not be further from the composer's intentions. We're not playing Beethoven or Korngold. We're playing our preconceptions about them. Which obviously is a rather rubbish thing to do.

Why is that relevant to sore arms? Well, it shows how our minds sometimes work. It becomes relevant when the attitude being expressed in professional performance is not to a piece of music, but to a person, and the issue is not playing a concerto or sonata, but treating a medical condition. What follows is not to denigrate the thousands of excellent, devoted and disinterested health workers who look after us all in difficult conditions day and night. It is one experience that occurred 30 years ago. I don't know how widespread such experiences are - but it seems unlikely that I'm the only person who ever encountered such a situation.

The correlation of physical to mental health - and, indeed, mental attitude - is powerful and merits the deeper investigation it has received in recent years, but it seems to be still much misunderstood. And it can work both ways. Blame the physical alone and you may miss a psychological component. But any tendency to blame the mind first and foremost would risk missing very real physical issues. In the year and a half I spent trying to recover from my tennis elbow - 1986-87 - I also came down with glandular fever. The first reaction from every practitioner I consulted in that town was that "it's all in the mind". I don't know how they'd reached that conclusion when all I'd said was that I was a second-year music student, I had a sore throat and a chronic fever and my arm hurt. They sent me to the university counselling service. I sat there saying I had a sore throat and a chronic fever and my arm hurt.

If you are a music student in a place notorious for its privilege, where everyone outside those walls - including, it appeared, some GPs and some 'alternative' practitioners - expect those from the university to roll in being entitled and stuck-up, it can be very difficult to get past this expectation. They don't see the actual person. They may not even see the injury. They see what they expect to see.

I tried the Sports Injuries Unit. Yes, there are designated hospital units for people who've sustained injuries pursuing a physical activity such as sport and they'll take remarkably good care of you if you've been playing rugby or rowing or whatever. But for a painful case of tennis elbow acquired through over-assiduous practising of the Chopin 'Revolutionary' Etude, you'd be shoved in a corner with a grudging ice-pack and some slightly ineffectual ultrasound, with tut-tutting because you haven't just injured yourself that day, you've been suffering for weeks (while you tried to get appointments for some treatment), and that's not really in their remit. The psychological message delivered with that ice-pack, surrounded by big chaps with "Football Is Life" t-shirts, is roughly: sports are good and a nice hobby, so we'll support that, but what do you mean

music is your life? "I got my sprain playing centre forward. What about you?" "Playing Chopin." "

Yer wot?" (The Eighties were a more polite decade than the present one, even at their most objectionable.)

Then I tried a chiropractor. I found myself facing a huge bloke from Yorkshire with a face like bacon and hands like beefsteaks, who said it was all in my neck - and proceeded to make certain that it would be. He should have been a butcher. I've never experienced, before or since, such pain at the hands of another human being (and I know I'm lucky in this respect), let alone someone who charged money for inflicting it. I remember coming out of that session dizzy and nauseous, knocking on the door of the nearest friend in the nearest college and almost passing out on her floor. Perhaps he was a rogue or a quack, I don't know, but I will never, ever try a chiropractor again.

Back in London for the holidays, I went to the family GP who'd known me since I was born. He did a blood test - which the university town GP hadn't done before sending me for counselling - and it revealed a virus of the glandular fever type. For that, there's not much you can do except take fever-reducing pain-killers and rest up with herbal tea. He prescribed anti-inflammatory pills for the arm, which helped a bit, if temporarily, and suggested a cortisone injection. I declined because a violinist in our circle of friends had had a cortisone injection in her arm for a similar problems: a mistake was made and she was left unable to play at all. But through our family GP I should probably have accepted it. I've had cortisone injections since then, carefully prepared by disinterested medical professionals with scans etc, for other problems that cleared up instantly as a result.

Still at home, I tried acupuncture next, doing a reasonable imitation of a porcupine splayed out on a table unable to free itself of its spines. They said it wouldn't hurt. It did. They said it wouldn't bruise. It did: I came out with a plum-and-charcoal-coloured hand. They said it would rebalance the energy to make the pain better. It made it worse. I've often been assured of the wonders of acupuncture since then, by some eminent musicians whose problems have been cured by it, but I think I'll give it a miss.

One day I went into a chemist to look at various on-the-shelf remedies in case I'd missed something. In a little book called 'Homeopathy for the Family' I found a recommendation for "pains in ligaments". I don't actually believe in homeopathy, but as I'd tried almost everything else, I thought I'd give it a whirl. I bought a little bottle of tiny white pills, which cost about £1.50. Two weeks later I was better.

I'm not recommending homeopathy, though. It hasn't worked for me for anything else since. I think the difference here was that at this stage I wasn't putting myself in the hands of people who, due to an institutional loathing of young people who dared to study music and play the piano, had quite possibly set out to make our conditions worse. Such an idea was absolutely unthinkable at the time. But looking back, I can't help wondering if that was the actuality behind the scenes.

My heart goes out to musicians who are suffering physical injuries and navigating minefields as they seek a solution. Today, three decades on from my experiences, the understanding of music as a physical pursuit that can give rise to physical injuries has been transformed and institutions such as the

British Association for Performing Arts Medicine,

Help Musicians UK, the

ISM and the

Musicians' Union, as well as the conservatoires themselves, are brilliantly organised and supportive if you are unlucky enough to need treatment, advice, counselling or financial aid for time off. But it's sobering to think that after 30 years, I am still angry about what happened to me then.

Meanwhile, I don't know what I've done to my shoulder, but I am leaving it to voltarol and co-codamol for a few days and will avoid heavy lifting for a week or two. At least now I don't have to practise the 'Revolutionary' Study.

If you've enjoyed this post, please support JDCMB at GoFundMe