Many thanks to Tasmin for sending this to me to run in full.

SPEECH GIVEN IN THE HOUSE OF COMMONS BY TASMIN LITTLE TO THE ALL-PARTY PARLIAMENTARY GROUP FOR MUSIC EDUCATION

on 2nd December 2015 to MPs, Lords and members of the music profession and teaching profession

|

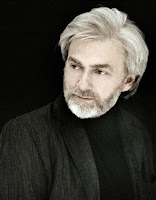

| Tasmin Little. Photo: Paul Mitchell |

Good afternoon. For those of you who don't know me, I'm Tasmin Little and I have worked as an international solo concert violinist for nearly 30 years. I've performed in every continent of the world, I have received a Classic Brit Award, a Gramophone Award and a Gold Badge Award; I am an Ambassador for The Prince’s Foundation for Children and the Arts, I have 4 Honorary degrees, a Fellowship of the Guildhall School of Music and Drama, and an OBE for Services to Music. A couple of weeks ago, I gave my 1500th professional performance.

I spoke here in 2013 to a committee of MPs on the subject of music education - and it's something I feel very strongly about, because I wouldn't be here addressing you now were it not for the fact that, when I was growing up in the early 1970's, my State Primary School in London employed a full-time violin teacher. I did not come from a musical background, but was lucky enough to have a teacher of quality who was able to recognise my talent. Any state primary school child should be able to aspire to my level of achievement but I do not believe they currently stand an equal chance of doing so.

During the 1980's, music education in this country took a nose dive and we are still recovering from an extended period when it was very far down the list of priorities. A whole generation missed out, not only on opportunities to enjoy playing and listening to music themselves, but, as many of them are now the teachers and parents of today, on the knowledge of what it can bring to their own children.

I believe that many people take for granted the importance of music - and fail to appreciate that it is an integral part of each and every person's life, whether they realise it or not.

It's an interesting exercise to imagine for a moment, a life lived without any music of any kind - 90 per cent of YouTube would no longer exist, Ipods would be semi-redundant, almost all Radio stations, as well as hugely popular television shows such as Strictly Come Dancing, Britain's Got Talent and The X Factor would be axed. Summer festivals such as The Proms, Latitude and Glastonbury, along with the majority of West End theatre shows, would disappear; Christmas would be devoid of carol singing, no-one would lock arms and sing Auld Lang Syne after the New Year chimes of Big Ben, The Pop Industry would be extinct, & films would consist only of talking, losing so much of the atmosphere and emotion induced by music. Ballet performances, catwalk shows, weddings, state ceremonies... and funerals would be seriously impoverished. I could go on and on...

This aural diet of dry husks would make each and every one of us yearn for the vast and varied panoply of music to nourish our ears, enrich our souls, and provide joy as well as comfort.

This is taking it to extremes as, in the context of most societies, there will always be music. Indeed the banning of music under rule of The Taliban and ISIS demonstrates how barren life would be without it. However, we are in danger in this country of putting music so far down the educational agenda that we risk not only diminishing the superb quality and status of those first class musicians who we have enjoyed up until now, but also losing a huge part of our cultural heritage.

We're all here because we believe in the importance of music in our lives and in providing high-quality music education in this country. But there really is a great deal more to be done in order to ensure that all children are receiving the best opportunities possible, and that we maintain the highest standards for our future generations.

Music is worthwhile in its own right, but I'd like to explain why music education provides so much more than the obvious. I'm hoping that you've all been given a list of 14 points which fill in more detail than I have time to talk about now. Please take this list away with you and peruse the information, as it is based on results of research taken from all over the world.

“Music improves cognitive and non-cognitive skills more than twice as much as sports, theatre or dance.” In addition, the study found that children who take music lessons “have better school grades and are more conscientious, open and ambitious.”

In addition to the sheer joy of playing music, there are so many additional benefits :

It improves reading and verbal skills, and helps children get good marks in exams.

It raises IQ, encourages listening and helps children learn languages more quickly.

It strengthens the motor cortex and improves working memory and long-term memory for visual stimuli. It helps people to manage anxiety, enhances self-confidence, self-esteem and social and personal skills.

It slows the effects of ageing! That's got to be good news!

It also encourages creativity – no surprises there.

This next one is a particular favourite as I have experienced this a great deal over the years... Learning a musical instrument encourages team building and, what's even better is, that these effects are not only felt by the pupils, but by the schools, and far into the wider community.

At the ground-breaking primary school in east London, Gallions, every child learns a string instrument – as a result, there are no discipline problems, no absenteeism from the staff, and no truancy, even though this school is situated in an area of social deprivation.

Finally, music also improves mathematical and spatial-temporal reasoning.

When you consider that these skills are highly prized by the government and are vital in a multitude of potential careers including maths, engineering, architecture, gaming and especially working with computers, it's fair to say that young musicians can pretty much succeed in any field they decide to pursue.

Which brings me to my next point – how music is perceived within the education sector. I spoke recently to the Head teacher at a nearby Grammar School and asked him why music education seems permanently to be at risk of being downgraded in the curriculum. His answer was: because it is not seen as a “facilitating subject”.

This really makes no sense at all, based on all the research and hard evidence of what music can provide.

So this surely begs these questions:

Why is this?

And, crucially, what can we do about it?

I think the first thing that needs to happen is that we must urgently invest in good teacher training. Sadly there are still many primary school teachers who are terrified to teach music because they themselves have not been taught the necessary skills to give their best – this situation is vastly unfair both on pupils and teachers.

In addition, I do believe that there are some Head Teachers who don't understand what music can bring to their school - and I had a direct experience of this myself a couple of years ago, at a time when I was visiting a great many schools during the course of an academic year at the invitation of a County Council.

Most schools were genuinely thrilled to have me there – however one primary school Head Teacher made it clear that my visit was a nuisance and interfered with important school routine. It was only after being incessantly pestered by the children whose classes I wasn't visiting, that she came in to see what I was up to - and finally asked me to play in the end-of-day assembly. To her credit, she was the first to start the rapturous clapping at the end, and her parting words to me were along the lines: “I'm sorry, I know I was unfriendly when you arrived but I've had OFSTED here all week and it's been so stressful. I thought your visit was the last thing I needed. But, in reality, it was the very thing that we all needed - the highlight of the whole week."

Whilst my story has a happy ending, there is clearly so much more work that needs to be done to ensure that teachers do not feel that music is a chore, and a box to be ticked.

I have visited hundreds of schools over the past 30 years and played to literally thousands of children of all ages, both here, and abroad in countries such as Zimbabwe and China, so I know what can happen when music is brought into the classroom and how the experience fuels the children's desire to make music themselves.

So I've been thinking about how to facilitate the stimulus of live music in schools, so that it becomes a regular event in schools. I've had an idea. What if a programme were developed within music colleges and universities whereby music students are given some training to go into schools to play and demonstrate their instruments, as well as chat to, the children – this would have a number of benefits: the primary school children would have access to high-quality music; it would enable young performers to gain important performance experience; it would give teachers ideas to build on for future classroom lessons and help them feel more comfortable with the subject; live music is very good for school morale; for those many musicians whose career will take them into teaching, the experience would be invaluable; and for those intending a career in performance, it would help equip them with the necessary skills now needed to successfully interact with audiences of all ages, and promote one's career.

Historically, our education system has been the envy of the world – and currently, thousands of pupils come from abroad to enjoy what our education can provide. I don't think this is because we teach English, maths and science better than any other country - it's because we are one of the few countries that truly provides a breadth and range of curriculum essential to give each individual the maximum chance to find and develop all their talents.

We have been a nation of innovators, precisely because of this - and historically, we have always valued that most important quality, creativity.

Einstein said - imagination is more important than knowledge

And when we think of all the people in the history of this country, who have made a difference on both an international and a domestic stage, the vast proportion were intensely creative. They were people who dared to challenge preconceived ideas, ignore the rules, and come up with radical innovations, both technological and artistic.

However, if the reasons I have provided thus far are not convincing enough, then let's consider the impact of music as a financial benefit to our economy.

UK Music has published an annual economic survey of music’s vast contribution to the UK economy. In 2014 the music industry contributed £4.1bn to the economy and the sector once again outperformed the rest of the British economy, with growth of 5% year-on-year; the industry provides 117,000 full time jobs; and music exports contributed £2.1bn in revenue .

So, although many people assume that our economic success depends on commerce alone, this is clearly not the case.

Even the Chancellor George Osborne seems to agree – he said recently:

“Britain’s not just brilliant at science. It’s brilliant at culture too. One of the best investments we can make as a nation is in our extraordinary arts, museums, heritage, media and sport. £1 billion a year in grants adds a quarter of a trillion pounds to our economy – not a bad return. So deep cuts in the small budget of the Department of Culture, Media and Sport are a false economy”

- but if this is the case and the Arts truly ARE valued in this way, then it is imperative that this is reflected and strengthened by their high visibility in the Ebacc curriculum. We will cease to be brilliant at these subjects if we do not nurture music and the Arts from the very start of the education system, and keep it high on the agenda right through secondary education.

In fact, I believe we've already begun to fall behind other European countries, as well as America, Scandinavia, China and the Asian Continent. In a recent leading international competition - one which has often been able to showcase outstanding young UK musicians in the past - there were no UK entrants of a high enough quality to enter even the competition's initial rounds, let alone get to the Finals and gain any prizes.” This is doubly depressing because it needn't be the case.

In October of 2013, neuroscientist Thomas Südhof was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology for his work in explaining the mechanisms of the presynaptic neuron.

Interestingly, he attributed most of his success to the qualities he learned from his early training in classical music, and the value of disciplined study, or repetitive learning, for creativity.

Music is a discipline - it requires patience, hard work, flexibility, understanding, teamwork, good communication skills and the ability to maintain concentration and really listen.

Wouldn't it be wonderful if all young people of today were able to truly learn these qualities and take them into their future?

I would like to end with a quote from Sophocles:

Whoever neglects the arts when he is young has lost the past and is dead to the future.

Below is a supplementary document:

Some of the benefits of learning music

Tasmin Little OBE

1. Music improves reading and verbal skills

Several studies have found strong links between pitch processing and language processing abilities. Researchers out of Northwestern University found that five skills underlie language acquisition: “phonological awareness, speech-in-noise perception, rhythm perception, auditory working memory and the ability to learn sound patterns.” Through reviewing a series of longitudinal studies, they discovered that each these skills is exercised and strengthened by music lessons. Children randomly assigned to music training alongside reading training performed much better than those who received other forms of non-musical stimulation, such as painting or other visual arts.

2. It improves mathematical and spatial-temporal reasoning

Music is deeply mathematical in nature. Mathematical relationships determine intervals in scales, the arrangement of keys and the subdivisions of rhythm. It makes sense then that children who receive high-quality music training also tend to score higher in maths. This is because of the improved abstract spatial-temporal skills young musicians gain. According to a feature written for PBS Education, these skills are vital for solving the multistep problems that occur in “architecture, engineering, maths, art, gaming and especially working with computers.” With these gains, and those in verbal and reading abilities, young musicians can pretty much help themselves succeed in any field they decide to pursue.

3. It helps children get good exam results

In a 2007 study, Christopher Johnson, a professor of music education and music therapy at the University of Kansas, found that “elementary schools with superior music education programs scored around 22% higher in English and 20% higher in maths scores on standardized tests compared to schools with low-quality music programs.” A 2013 study out of Canada found the same. Every year that scores were measured, the mean grades of the students who chose music were higher than those who chose other extracurriculars. While neither of these studies can necessarily prove causality, both do point out a strong correlative connection.

Surprisingly, though music is primarily an emotional art form, music training actually provides bigger gains in academic IQ than emotional IQ. Numerous studies have found that musicians generally boast higher IQs than non-musicians.

5. It helps children learn languages more quickly

Children who start studying music early in life develop stronger linguistic abilities. They develop more complex vocabularies, a more nuanced understanding of grammar and higher verbal IQs. These benefits don’t just impact children’s learning of their first language, but also their ability to learn every language they attempt to learn in the future. The Guardian reports: “Music training plays a key role in the development of a foreign language in its grammar, colloquialisms and vocabulary.” These heightened language acquisition abilities will follow students their whole lives and will aid them when they need to pick up new tongues late in adulthood.5

6. It encourages listening

Musical training makes people far more sensitive listeners, which can help tremendously as people age. Musicians who keep up with their instrument enjoy a much slower decline in “peripheral hearing.” They can avoid what scientists refer to as the “cocktail party problem” in which older people have trouble isolating specific voices (or musical tones) from a noisy background.

7. It will slow the effects of aging

But beyond just auditory processing, musical training can also help delay cognitive decline associated with aging. Some of the most promising research positions music as an effective way to stave off dementia. Studies out of Emory University find that even if musicians stop playing as they age, the neurological restructuring that occurred when they were children helps them perform better on “object-naming, visuospatial memory and rapid mental processing and flexibility” tests than others who never played. The study authors add, though, that musicians had to play for at least 10 years to enjoy these effects. So this adds even more weight to the argument in favour of starting children early and continuing with music lessons during high school.

8. It strengthens people's motor cortex

All musical instruments require high levels of finger dexterity and accuracy. The training works out the motor cortex to an incredible extent, and the benefits can apply to a wide range of non-musical skills. Research published in the Journal of Neuroscience in 2013 found that children who start learning to play before the age of 7 perform far better on non-musical movement tasks. Exposure at a young age builds connectivity in the corpus callosum, which provides a strong foundation upon which later movement training can build.

9. It improves working memory

Playing music puts a high level of demand on one’s working memory (or short-term memory). And it seems the more one practices their instrument, the stronger their working memory becomes. A 2013 study found that musical practice has a positive association with participants’ working memory capacity, their processing speed and their reasoning abilities. Writing for Psychology Today, William R. Klemm claims that musicians’ memory abilities should spread into all non-musical verbal realms, helping them remember more content from speeches and lectures. Good news if you want a career in politics.

10. It improves long-term memory for visual stimuli

Music training can also affect long-term memory, especially in the visual realm. Scientists at the University of Texas at Arlington reported last year that classically trained musicians who have been playing more than 15 years score higher on pictorial long-term memory tests. This “heightened visual sensitivity” likely comes from parsing complex musical scores.

11. It helps people to manage anxiety

Analyzing brain scans of musicians ages 6 through 18, researchers out of the University of Vermont College of Medicine have found tremendous thickening of the cortex in areas responsible for depression, aggression and attention problems. According to the study’s authors, musical training “accelerated cortical organization in attention skill, anxiety management and emotional control.”

12. It enhances self-confidence and self-esteem

Several studies have shown how music can enhance children’s self-confidence and self-esteem. A 2004 study split a sample of 117 fourth graders from a Montreal public school. One group received weekly piano instruction for three years while the control received no formal instructions. Those who played weekly scored significantly higheron self-esteem tests than those who did not. High levels of self-esteem can help childrengrow and develop in a vast number of academic and non-academic realms.

13. It encourages creativity

Creativity is notoriously difficult to measure scientifically. But most sources hold that music training enhances creativity “particularly when the musical activity itself is creative (for instance, improvisation).” According to Education Week, Ana Pinho, a neuroscientist at the Karolinska Institute in Stockholm, found that musicians with “longer experience in improvising music had better and more targeted activity in the regions of the brain associated with creativity.” Music training also enhances communication between the right and left hemispheres of the brain. And studies show musicians perform far better on divergent thinking tests, coming up with greater numbers of novel, unexpected ways to combine new information.

14. It encourages team building and these effects are not only felt by the pupils but by the schools and far in to the wider community.

But most of all: It is musical, and important in its own right as its own subject, its own discipline and its own artistic, intellectual, academic, professional career path.