Late last night the tragic news reached me that the great Chinese pianist Fou Ts'ong has died, aged 86, of Covid-19. This phenomenal artist was part of my childhood, as from the age of 10 to 17 I studied piano with his wife, Patsy Toh. He would flit by occasionally, a somewhat shy and shadowy figure in a doorway or in the hall, and my small self was rather terrified of him. I knew little of his story then, nothing about the horrific fate of his family in the Chinese Cultural Revolution or his dramatic escape via Poland after the Chopin Competition - though I did know he was friendly with Richter, because I once turned up for a lesson to find that Richter was there in the house, practising Schubert. Finally, as editor of what was then Classical Piano Magazine in the 1990s, I had the chance to interview him on the occasion of his 60th birthday. I asked him one question and he talked for two hours. Fortunately I still have the text, so I am rerunning it below in tribute to him.

|

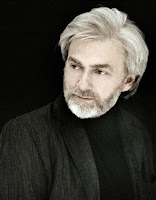

Fou Ts'ong

(Picture source: Svensk Konsertdirektion AB Website) |

"I am always a beginner. I am always learning..."

Fou Ts'ong tells Jessica Duchen the extraordinary story of his childhood in China and his escape to the West

Fou Ts'ong's life and career have been unconventional in almost every way, sometimes spectacular, sometimes unobtrusive, yet always sincere, taking him from the cosmopolitan Shanghai of the 1930s through Poland in the 1950s to the shores of Lake Como in the 1990s. There, under the auspices of the International Piano Foundation, he works with other eminent teachers and a select group of the best young pianists, creating, as he puts it, "the Davidsbündler of our time".

Fou talks with great enthusiasm (and an astonishing gift for mimicry) about his childhood and the early part of his career. This world could not have been more different. "My childhood would have been peculiar anywhere," he begins, "but was especially so in China, then a country of 450 million people over 90% of whom were peasants and the small core of intellectuals a tiny percentage." Fou belonged to that minimal number, being the son of a leading Chinese scholar, Fu Lei, who, having travelled freely to Europe and studied in Paris for five years, was exceptionally equally well versed in both Classical Chinese and modern philosophy. Among his works he counted the translation into Chinese of Romain Rolland's immense and influential novel Jean Christophe and the complete works of Balzac. [Fu Lei's Family Letters, a best-seller in China, published the correspondence of father and son and the progress of the youthful musician's piano studies.]

"Jean Christophe was an enormous influence in China, much more so than in Europe," explains Fou. "I think that was because it represented the liberation of the individual. To the Chinese this is the crucial issue - to this day it is not solved. My father was an extraordinary person, a renaissance man of great humanism; that is the way I was brought up. I was taught classical Chinese from a very early age by my father himself and this kind of classical education even in my generation is very rare. And my father, when he was teaching me Lao-tse or Confucius, would also quote Aristotle or Plato or Bertrand Russell or Voltaire."

"Those were very frenetic years in China, we were under Japanese occupation from 1941-45 - and for four years my father never went out of the house. There was hardly any food, just very coarse rice. Very hard times, but also it was a very hopeful time because the whole of China was in a ferment; everybody felt that fascism was evil, and evil and good were very clear cut. We were good, so we fought for the cause."

Fou's family also possessed a large number of records of classical music. Fou grew up to the sounds of artists such as Alfred Cortot, Edwin Fischer, Wilhelm Furtwangler, Pablo Casals. From a very early age he was mesmerised by music, yet it was not until he was 17 years old that he began to take the piano seriously as the focus of his life. Early lessons when he was ten were given by a pupil of his father, a young woman who had studied with a Russian pianist in Shanghai. Her loving and encouraging approach provided "the greatest joy in my life" for the otherwise strictly reared child. He progressed by leaps and bounds, but when he was sent instead to the Italian pianist and conductor Paci, one-time assistant to Toscanini at La Scala Milan and the founder of the Shanghai Municipal Orchestra - who had "got stuck" in Shanghai thanks to a passion for gambling - he found himself facing a very different approach which took all the joy away. He was given nothing but exercises to play for a year, plus the indignity of balancing a coin on the back of the hand.

After the family moved to Kuming in Yunan province, Fou became a rebellious teenager, passionately committed to the idea of communist revolution. His father, among the first Chinese to realise the truth about Stalin and the lies of Bolshevik communisim in Russia, acted as "a Cassandra of his time" and foretold disaster. His son disagreed and eventually a family split ensued. His father went back to Shanghai while Fou, alone in Yunan, was thrown out of school after school and finally, running out of schools and excuses, applied to and was accepted at the University of Yunan at the age of 15. He enrolled for English literature but spent his time "making revolution all over the place, falling in and out of love all the time, drinking and playing bridge!"

But word got out that he could play the piano. When two rival churches in the town both put on Handel's Messiah at Christmas they competed for Fou's services as accompanist. Fortunately the performances were on different days, so he played for both. By exam time he was terrified, having done no work. Instead, he put on, with the help of fellow students, a concert in one church where he played an album called 101 Favourite Piano Pieces from cover to cover on a wartime upright. At the end a collection was made for him and immediately he had enough funds to make his way back to Shanghai by himself to continue his musical development.

The 17-year old thoroughly impressed his father with his difficult two-month solitary journey; his father agreed to help him pursue studies with the aim of becoming a concert pianist. These took on a distinctly surprising slant as Fou had very few lessons; one piano teacher emigrated to Canada after three months; next, what lessons he did have were from not a pianist but a violinist, the aging Alfred Wittenburg, a refugee from Nazi Germany, ex-concert master of the Berlin Opera and chamber music partner of Artur Schnabel. After Wittenburg's death, "I studied by intuition, thinking and reading books. I studied on my own and made my debut one year later. In Shanghai that made such a stir that central government, who wanted to send someone abroad for a competition, came to Shanghai to search out for me as one of the candidates."

That was how Fou went to a competition in Bucharest, where he won third prize, and then, fatefully, to Poland, where the government sent Andrzej Panufnik himself to listen to him to find out if he was worthy to participate in the Chopin Competition Panufnik raved, "and soon everyone in Poland was raving. 'Have you heard him play mazurkas? Listen to those mazurkas!' I became a sort of performing monkey, everyone was asking me to play mazurkas all the time!" Fou laughs. He duly entered the competition and won the mazurka prize.

https://youtu.be/SqFOylOw2Ls

After the competition Fou studied in Warsaw and Cracow, thriving on the enthusiasm and encouragement he received there and falling in love again, this time with Mozart, an affair which lasts to this day. Professor Drzewicki, who also taught Halina Czerny-Stefanska and Adam Haraciewicz, sat and smiled through Fou's lessons. "After the competition he told me, 'Ts'ong you are different, you are so original and personal, you should only come to my lesson maybe once a month, no more'. Altogether I can count on my fingers the number of times I went. He said, 'I am here only to guide you if you go out of way'.

"I was a great counterfeiter because I managed to hide all my troubles by my unique way of fingering, by my imagination, somehow by hoping to produce the goods. I always wanted to realise whatever vision I had in my head - in what way I don't know, I found it in my own way. Unless the vision was presented in a way that didn't show its deficiencies I would not allow it to go out. In a way I am my own downfall because I camouflage so well. In some ways it's also good because my way is original. But the struggle I have had with pianistic problems over the years is unbelievable, even to this day. I have to practise awfully hard; I envy pianists who have a great facility because I wish I had more time to play more music. Musically I am very greedy!'

Fou extended his stay in Poland as long as he could, for by then it had become dangerous for him to return to China where the anti-rightist movement - "the dress rehearsal of the Cultural Revolution" - had begun, and condemned him and his father. "It was a matter of life and death." He was desperate to go to Russia where a new friend and supporter was doing his best to offer help: Sviatoslav Richter, who wrote an enthusiastic article about Fou for a communist magazine entitled Friendship, published jointly in Russia and China. Richter had hoped thus to help Fou come officially to Russia, but while the article appeared in the Russian edition, the Chinese never carried it; nothing came of the scheme. Fou did not learn of this episode until many years afterwards.

His dramatic escape to Britain was made possible by the help of some more eminent beings: Wanda Wilkomirska, who helped to persuade the Polish authorities to "look the other way"; a music-loving wealthy Englishman named Auberon Herbert, who helped arrange an invitation for Fou to play in London, for which he could obtain a visa; and the pianist Julius Katchen, who lent him the air fare. To help throw the Chinese authorities off the scent, a "farewell"concert was announced at the last minute; Fou Ts'ong would perform two concertos, Mozart 's C major K503 and Chopin's F minor (both of which he learned in a week - on Saturday evening, 23 December. Another red herring, a farewell recital, was also announced for a later date, though pianist and organisers knew it would never happen. Early the next morning - a Sunday and Christmas Eve in a strongly Catholic country, a day on which "even the most diehard military police will become a little bit lax!" - Fou Ts'ong took a British Airways plane to London. He was free and an immediate celebrity in the West. Caught in the Cultural Revolution in China, Fou's father and mother both committed suicide.

Today, looking back over this extraordinary story and his varied fortunes since that time, Fou has some sensible advice to offer young would-be pianists. "First, you must have good self awareness, to know what you're made of. If you really have got it in you, not only talent but real aspiration, that means you are ready to sacrifice your life for it, totally dedicated to it, that's almost more important than talent. And even with these two, you have to be prepared to get nowhere in terms of worldly 'success'. You must know what you're in for! I wouldn't advise anyone to go on for the wrong reasons.

"I consider myself terribly lucky, although I wouldn't consider my career that easy, partly because I have my deficiencies, also partly and largely because of my character. My wife Patsy [pianist and teacher Patsy Toh] says to me, 'You shouldn't complain, because you made your own destiny'. And that's true. Today I think to myself, thank God, now I'm really beginning to understand music. But I consider myself a beginner. I am always a beginner. I am always learning. I think I am very lucky that I never had so much success that I could be blinded by vanity. And to be in music, you are very lucky. When I was very young, I wrote to my father from Poland that I was sad and lonely. He wrote back: 'You could never be lonely. Don't you think you are living with the greatest souls of the history of mankind all the time?' Now that's how I feel, always."